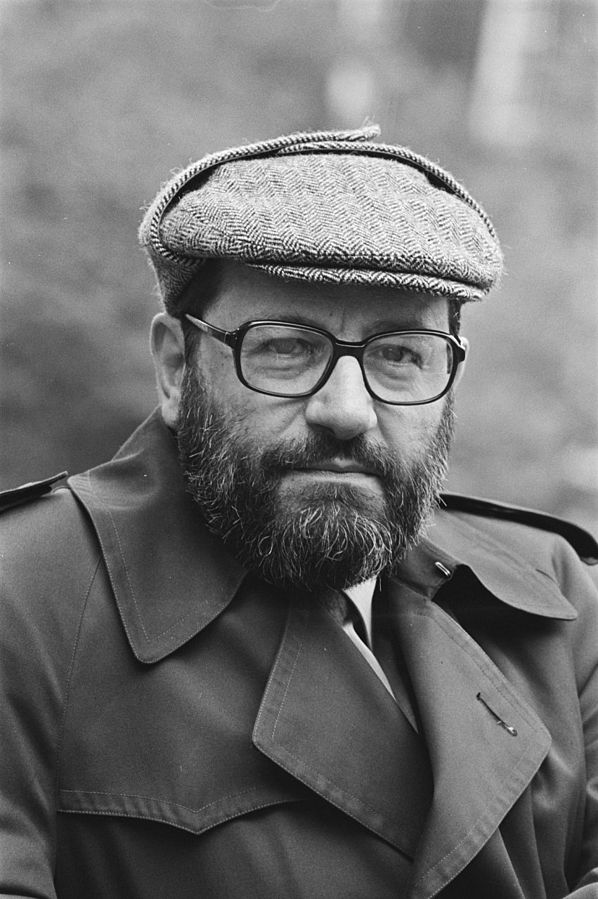

I never met Umberto Eco. The closest I ever got was collecting tickets booked under his name in Milan’s central railway station. “I am here to collect some tickets” I said, and the clerk replied:

“What name?”, and then with nonchalance I said:

“Eco, Umberto Eco”.

The clerk’s eyes lit up. Not looking much like Umberto Eco, the clerk asked whether I was part of the Eco family or working for them, and I said I was a friend of Eco’s daughter C., with whom I had swapped tickets for a weekend escape to Rome from our life as colleagues in a Milan architecture office. In passing C. would occasionally refer to photos on newspapers of her literary parents by saying “Che tristi..” In colloquial English it could be translated as “What saddos…”, implying that from a daughter’s perspective a life immersed in a home library and a word processor did not seem as exciting as it was perceived by everybody else, or maybe she was just being humble about her dad’s fame, given we were in Italy, where of course he was considered by many, yet certainly not all, to be a kind of national treasure.

At that time I was addressing the pros and cons of the life I had in London versus the life I had in Milan, and C., having an Italian father and German mother was very categorical, “I have lived a similar decision time between Germany and Italy in my own life” she said

“And I have chosen Italy, and have no doubts about my choice”.

I feel for C. and hope she will be able to navigate this new time in her life without her father in a way that is as philosophical as some of her father’s texts.

For me his most important text is a very short one. It is called “Eternal Fascism, Fourteen Ways of Looking at a Blackshirt” and I rate it highly because in these times in which we are told we can’t use this “F” word as it belongs exclusively to twentieth century Spain or Italy, Eco had the courage to disagree, and said what I fear to be true: fascism is both ancient and eternal, the fight against it will never end. This below, to give a brief insight into his ideas, is a summary of Eco’s fourteen ways of recognising fascism. Eco said that all it takes is just a single one of these fourteen characteristics to be present in order for a fascist nebula to start forming itself:

- The cult of traditions, especially the combination of different and contradictory traditions. Primeval truth has already been found and can’t be improved upon

- Traditionalism as a rejection of modernism and rationalism. Irrationalism

- The cult of action for action’s sake; a distrust of the intellectual world

- Disagreement is treason

- Fear of difference

- A frustrated middle class frightened by the pressure of lower social groups

- To be born in the same country is the only privilege of the masses. Enemies are the only thing that unifies the nation.

- Humiliation by the richness or power of the enemy. Due to an oscillating rhetorical register, enemies are at the same time too strong and too weak. Fascisms are condemned to lose all their wars as they are incapable of an objective analysis of the strengths of their enemies.

- Life as permanent warfare; pacifists are collaborators with the enemy

- Popular elitism: every citizen belongs to the best people in the world. Everyone on the hierarchical ladder despises those below, as in a military organization.

- Machismo, intolerance and condemnation of nonstandard sexual habits, love of weapons as displacement of sexual pleasure

- The cult of heroism, linked with the cult of death. Heroism as the everyday norm. Heroic death advertised as the best reward for a heroic life. Impatient “heroic” actions leading to the death of others

- Ur-Fascism is based on ‘qualitative populism.’ In a democracy the citizens enjoy individual rights, but as a whole the citizens have a political impact only from a quantitative point of view (the decisions of the majority are followed). For Ur-Fascists individuals have no rights, and the ‘people’ is conceived of as a monolithic entity that expresses the common will. Since no quantity of human beings can possess a common will, the leader claims to be their interpreter. The people is thus a merely a theatrical pretence. In our future there looms qualitative TV or Internet Populism, in which the emotional response of a selected group of citizens can be presented and accepted as ‘the voice of the people’.

- Orwellian Newspeak: an impoverished vocabulary, and an elementary syntax, in order to limit the instruments for complex and critical reasoning. Eco here warns us that ‘we must be ready to identify other kinds of Newspeak, even if they take the apparently innocent form of a popular talk show’

What he pointed out above goes against all the post Orwellian arguments that the word fascism is overused and has lost its meaning; Eco argued that it would never lose its meaning. Eco warned that the new fascism would emerge in plain clothes , it would look nothing like the last one, this time it could be camouflaged behind political correctness, a smiling face and business attire. Eco wrote:

It would be so much easier for us if there appeared on the world scene somebody saying, “I want to reopen Auschwitz, I want the Blackshirts to parade again in the Italian squares.” Life is not that simple. Ur-Fascism can come back under the most innocent of disguises. Our duty is to uncover it and to point our finger at any of its new instances — every day, in every part of the world. Franklin Roosevelt’s words of November 4, 1938, are worth recalling: “If American democracy ceases to move forward as a living force, seeking day and night by peaceful means to better the lot of our citizens, fascism will grow in strength in our land.” Freedom and liberation are an unending task.

Eco is no longer with us, but I fear his warning is coming true. To those who believe the fight against fascism was won in Italy and Spain seventy years ago, he said “Wait, think”. Eco offered fourteen ways of recognizing contemporary fascism, and I believe his fourteen points towards an identification of eternal fascism – which he called Ur-Fascism – or variations on them, will, as he premised them to, be valid for a long time to come. The themes of The Name of the Rose may not seem directly relevant to contemporary discourse one day, but Eco’s identifications of fascism will always be relevant if human nature remains what it is today and has been for thousands of years. The first step is to acknowledge that this time we are not speaking about Italy or Spain, we are not speaking of Mussolini or Franco. Once we accept that, we will be ripe to embrace Eco’s warning that our fight against eternal fascism has, unfortunately, probably only just begun.

By Robin Monotti Graziadei

Further reading: see Eco’s ‘Fourteen Ways’ and other writings including `Migration, Tolerance, and the Intolerable’ in his collection Five Moral Pieces